Lilla Ecséri

“I am Roman Catholic, but only recently”

Lilla Ecséri was born in Budapest in 1928 to an affluent middle class family. Her ancestors included the Kánitz family from Eger, one of the most reputed Jewish families of the town. Lilla inherited her family name from her grandfather, Dezső Kánitz a banker and leader of the Jewish community. Kánitz was ennobled in 1910 and awarded the name ’nagyecséri’ (of Nagyecsér). His son, László Kánitz a decorated WWI veteran adopted the name Ecséri. He was Lilla’s father. As prominent citizens of the town of Eger, Dezső Kánitz and his younger brother, Gyula, a lawyer were dragged away, held hostage and beaten up by the red guards in 1919 during the days of the Communist Hungarian Soviet Republic. On her maternal line, Lilla’s ancestors came from a family no less reputed: she was related to the crop merchant Turay-Schossbergers.

The Ecséri family converted to Christianity in the early 1940s. “My religion (which is the most important thing these days): I am Roman Catholic (but only recently), not to my shame, but to my inconvenience, of Jewish descent.” wrote Lilla in her diary with bitter irony. The girl was enrolled in Veres Pálné Gimnázium, a secular high school. She had lived a more or less undisturbed life up until the German occupation. She was making plans for the future, was preoccupied with her love life: “as for my future career, as ridiculous as it may sound, I want to become a movie actress and nothing else. … About boys: a 16-year-old girl is supposed to have a suitor already. I do not have and have never had one.”

Occupation and yellow-star houses

The occupation of Hungary by the Germans in 1944 changed everything. Their seven-bedroom apartment in the city center was seized by the army, the family had to move. Relatives, friends were arrested one after the other. “God! We live in a lousy world” – noted the 16-year-old teenager in her diary. News about the deportations from the countryside spread fast. Lilla put down the following lines on June 9: “I can’t believe I must die now when I haven’t even lived yet. But rumor has it that unless something miraculous happens, soon we’ll be taken to our death in sealed cattle cars. It has been already done outside of Budapest”

By early July, Jews in fact could only be found in Hungary in labor service units and in Budapest. As per the German-Hungarian plans, the deportation of the Jews of Budapest was going to happen next. The concentration of people before deportation took place during June. Hungarian authorities crammed the Jews of Budapest, numbering some 200,000 into more than 2,000 buildings scattered across the city.

The Ecséris had to move too. Deportations were imminent and everyone was expecting it tensely. They almost began twice (early July and late August), but something always stood in the way in the end. First, Regent Horthy put a halt on deportations due to international protests. In late August, Romania swapped sides and joined the Allied Forces radically changing the political and military situation. As the war situation deteriorated, the Germans no longer forced the deportation of Budapest Jews. Many of those arrested earlier were released from prisons and internment camps. Strict curfew rules were loosened for the fall Jewish holidays. Jews began to hope they may evade the fate of their countryside brethren.

Slave labor

On 15 October 1944, Horthy announced that Hungary would quit the war.German Nazis however took the initiative again, ousted Regent Horthy and helped Ferenc Szálasi’s Arrow Cross Party to power. “After the joy of yesterday, the whole building is now in panic” – wrote Lilla the following day. “I am convinced that in the end, we will survive this thing. I am absolutely relaxed and phlegmatic about all this. I am convinced that we are going to survive this. If we are not, the worst thing that may happen is that I am going to be deported and killed (I do not think this too probable though)”.

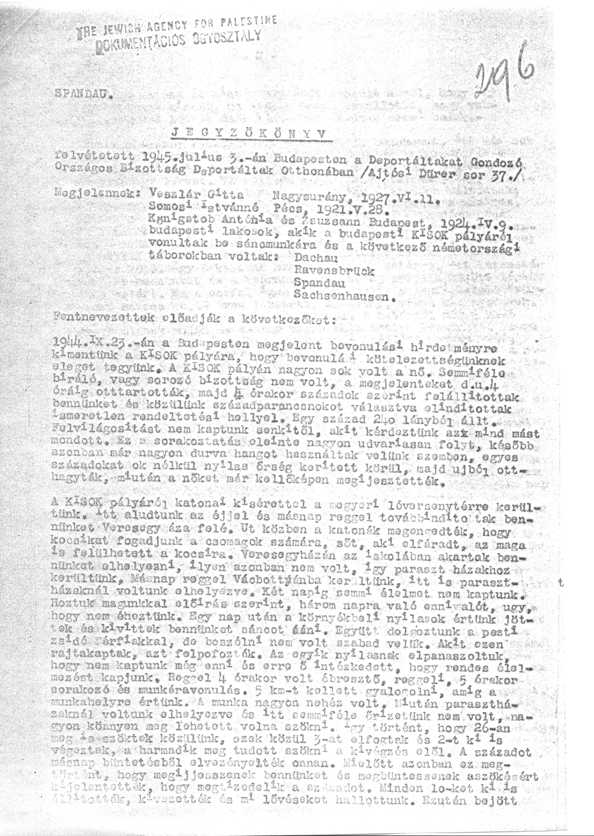

Lilla, with many other women, was deported and assigned for a so-called “trench digger company”. She worked in Budapest, built ramparts, did earthwork in inimical conditions. Twenty-year-old Zsuzsanna Königstop was deported from Budapest in a similar company. “We had to wake up at 4 am, morning quarters was at 5 am and then marching to work. We had to walk five kilometers to get to work. Labor was strenuous. Since we were lodged in farmhouses without any guards, we could have escaped easily”. Some did run away “three of those were caught and two executed”.

Hiding and survival

Most trench diggers were deported to German concentration camps in November-December, Lilla was fortunate though and managed to go back to the capital. From then on, she was moving from house to house, from apartment to apartment hiding from Arrow Cross militiamen. She showed up in the so-called “international ghetto” and in other places as well, often evading raids and deportation by only a few hours. Fleeing was made especially difficult by Lilla’s appearance “I have a very Jewish complexion; I hear that all the time. It felt terrible today, when someone told me [from among those she was hiding with in a cellar] not to go up, they will immediately see who I was”.

During the Arrow Cross era, a 16-year-old young girl was also exposed to the danger of being raped. Militiamen committed sexual violence on a mass scale. Raping women was routine conduct for the Arrow Cross of Zugló as it was for other militiamen in the 12th District or other areas. Armed men patrolling the international ghetto in the Újlipótváros neighborhood raped their victims in abandoned train cars at the Nyugati Pályaudvar (Western Station). They sometimes even raped women before shooting them into the Danube.

Lilla depleted all her physical and mental resources by the end of December 1944. “We are soon entering the new year. Separated from my parents, I am sitting in an alien place the whole day, a dark shelter where I can hardly see anymore … I could write a lot, but both the paper and the candles are in declining supply. I am heartbroken for this wasted life and think back to this time a year ago, how happy I was then. And I have never partied in my life, and I am already sixteen. I am looking for a happier new year” She lived through the last weeks hungry and cold, in the shadow of death in a hospital in Buda. Dozens of Jewish children and teenagers, including Lilla Ecséri, were rescued by the Swedish Red Cross in the Institute for Special Need Education with the consent of the management.

The girl survived; her mother however did not live to see liberation. “My mother died!!” – she wrote in her diary in despair “I cannot sit in anyone’s laps anymore; I cannot cry my pain for anyone anymore and no one will ever put her soothing cool palm on my throbbing forehead. I am alone. I am suffering. I have never suffered this bad. You do not see this. Please help. I have to live and suffer, while I am dying of it.”