Child slaves in Auschwitz

Those Hungarian children and teenagers who survived the selection upon the immediate arrival at Auschwitz-Birkenau were taken to the camp bath, the so-called Sauna, together with the adult prisoners. Sorted by gender, there they had to undress completely – their hair was shaven all over their bodies. A quick shower followed in front of the SS guards. To replace their own clothes, they have received striped prisoner uniforms or the clothes left behind by those who had been murdered already. No one paid attention to giving them the right sized clothes or shoes. Afterwards the scribes registered the personal data of the new arrivals who then were tattooed. A brief quarantine period followed and the deportees were transported to various camps of the Auschwitz complex to perform slave labor.

The Monowitz camp (Auschwitz III) was located a few kilometers from Birkenau (Auschwitz II). Prisoners incarcerated here worked on one of the largest German constructions in WWII – the vast synthetic rubber and petrol plant of the chemical industry giant IG Farben.

The camp was referred to as “Buna” by the prisoners. Thousands of Hungarian boys and men were transported to the immense construction site in the summer of 1944. Among their ranks was Dr. Miklós Nyiszli, the Transylvanian physician, who later performed autopsy for Dr. Mengele. “Hundreds of freight cars arrived every day” – he remembered later – “carrying bricks, cement and iron blocks. Offloading is always the most urgent task. Prisoners perform it at an inhumane speed …They do it at the double. Six bricks laid on each other in the hand; cement sacks weighing 50 kilograms each on the shoulder; four-meter-long iron pole with eight centimeters in diameter on the shoulders of two men; one piece of thick cable weighs circa hundred kilograms. Many faint and collapse from heavy work and empty stomach, and many is killed by heart failure – quick and benevolent end of suffering. The last respects paid to the deceased here is equal to being thrown into the cable ditches. Soil is laid on them, then comes the cable and eventually concrete is poured over.” Those suffering an injury or becoming ill or emaciated were sent back to the gas chambers of nearby Birkenau.

Further thousands were transported to dozens of subcamps erected around Auschwitz. For many, slave labor meant escape from death only temporarily. The official working hours were from 6 am to 5 pm. As the mornings started and the evenings concluded with roll call lasting many hours, prisoners could rest only 5 to 7 hours. Factories and mines of varying size were built in the region. The prisoners worked in these under terrible circumstances. They were constantly beaten by the SS and the work supervisors (capos, foremen) selected by the SS from the prisoners’ ranks. Working the slave laborers to death was an integral part of the Nazi to plan to destroy Jewry. The SS received a few Marks (Nazi currency) per prisoner and day for the cheap labor. More for strong men and craftsmen, less for women and unskilled labor. The profit was guaranteed by the fact that the SS spent only 1 to 1.5 Marks on a prisoner per day. In reality it was even less as the SS guards and the capos frequently stole the prisoners’ rations.

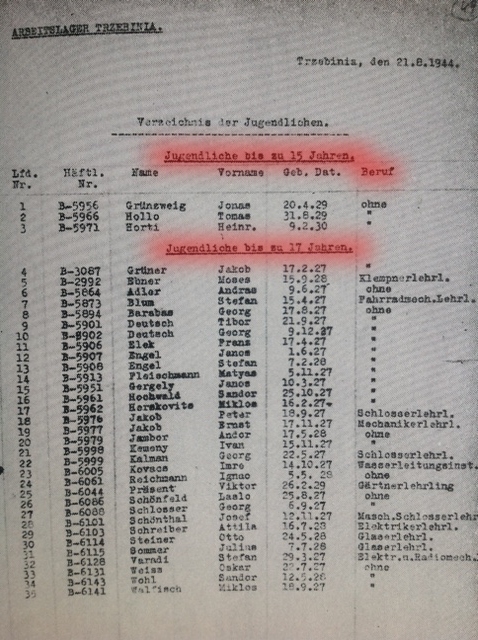

More than 400 Jews performed slave labor in the Trzebinia subcamp that was located 22 kilometers from Auschwitz. At least 120 under-seventeen prisoners worked on clearing the rubble of an oil refinery destroyed by air raids. As the surviving name lists attest, many of them were Hungarian, for example, Tamás Holló (age 15, prisoner number B-5966), György Barabás (17, B-5894), Mátyás Fleischmann (17, B-5913), János Engel (17, B-5906), Miklós Herskovits (17, B-5962), Iván Kemény (17, B-5998), Imre Kovács (17, B-6005), Attila Schreiber (16, B-6103), István Váradi (17, B-6128), SándorWohl (16, B-6143).

To intensify the speed of the work, SS men and capos regularly beat the prisoners. They were given scarce food supply; they wore only a thin uniform and wooden shoes; there were very little sanitary facilities. It is no surprise that 15 to 30 percent of the prisoners on average were sick or injured. Those incapable of working were sent back to Auschwitz-Birkenau where they were murdered or killed off by diseases and hunger. Two hundred people who were killed in Trzebinia were incinerated in the subcamp’s own crematorium.

A survivor from Budapest remembered as follows: “Those too weak to work were stripped naked, put, or rather thrown, onto a car and taken to the crematorium. Poor fellow on the truck knew what was awaiting him, but it’d be a mistake to think he despaired. We were in such a state that the crematorium seemed like salvation. We constantly talked about suicide, but we were too weak mentally and physically to even do that, as killing yourself requires energy we didn’t have.”

Many 14-to-16-year-old boys were among the Hungarian prisoners of the subcamp Eintrachthütte. Some of them worked in the armament factory where they made anti-aircraft weaponry. Others were taken to external locations. Sixteen-year-old Pál Schlesinger from Kaposvár performed slave labor in the factory: “We could not step away from the machine because the workload was set so we couldn’t really talk. The first level of supervision was the Häftling-Vorarbeiter (foreman), who usually was an Aryan (non-Jewish) Pole; then came the German Meister (master), a usually unpleasant and mostly cruel civilian; the next one was the Kommandoführer who was an SS and there was also the capo who was also a häftling (prionser). If someone could not perform the standard quantity, he was reported for sabotage and got 20-25 blows with the rod.”

Eighty people were crammed into one room in each barrack. They wore prisoner uniforms and wooden shoes, but no underwear. They could use only cold water to wash themselves, but they received clean clothes once a week. The accommodation was relatively clean: the prisoners laid on straw mattresses and could use two blankets each. The food supply consisted of coffee, 25-30 decagrams of bread and various additions. “Compared to Birkenau we were very well off” – remembered 15-year-old Gyula Berger from Komárom.

Children who broke the draconian rules were handed over to the local Gestapo. Jenő Fried, 15 years old, could not bear hunger anymore. Therefore he smuggled cigarettes into the factory to trade it for bread with the civilian workers. He was caught and he had to stand erect for a whole day among the electric barbed wire. He spent further hours in a standing cell flooded with water. He managed to stay alive somehow, but he had to be taken immediately to the hospital.

Andor Guttmann from Aknaszlatina was only 14 when we was taken to Eintrachthütte. Despite his young age, he stayed alive – only because an SS guard grew to like him and clandestinely smuggled food for him.

The survival rate of the child slaves was especially low if they were taken to one of the coalmines of the area. Subcamp Jawischowitz was ten kilometers from Auschwitz and ca. fifty Hungarian boys around the age of 14 were assigned there. They were accommodated in crowded barracks and though they could bath daily and they have received new clothes on more than one occasion, their hunger was constant.

Most of them mined and loaded coal. An average prisoner’s body gave up after three or four months due to the long shifts, lack of protective clothing and skills, the brutality of the guards, workplace accidents and poor supply. Those who became incapable of working were sent back to the gas chambers of Birkenau. “They were thrown onto the trucks naked, like dogs”. – remembered 17-year-old Bernát Paszternák who had been deported from the Carpatho-Ruthenian town, Felsővisó.

Hundreds of Hungarian Jews worked in the coalmine of the Charlottengrubesubcamp. They were handpicked by the mine director in Birkenau. Mainly Transylvanians were taken here. Their food supply was very bad – many times all they had to eat was frozen kohlrabi. Accidents at the worksite as well as inflammations of wounds were frequent. Various diseases also claimed plenty of lives. Half of the prisoners became unfit to work in less than a month. 17-year-old Miklós Heller from Galgóc was deported to Auschwitz with his family. His mother, two little brothers and younger sister were murdered immediately upon arrival. The SS physician sent Miklós and his father to slave labor. Both of them were assigned in a labor transport to Charlottengrube where they were taken to the coalmine. “The constant dark was terribly depressing for me … The skips are coming and going – they run on electricity like trams. We were also made sit into one of these cars. I liked this very much and I found it interesting.” Miklós and the other prisoners shoveled coal all day. Soon his father got injured. Due to lack of proper care, his wound got infected. He died in early December in the hospital.

“I stayed here all alone by myself” – concluded Miklós after liberation.

A fürstengrubei altábor szénbányájában 150 magyar zsidó robotolt. A május végén beérkező transzportokból válogatták ki őket. A visszaemlékezések szerint sok volt közöttük a 14-18 éves fiú. Egy részük a bányában dolgozott, mások új tárnát ástak, síneket raktak le, erdőt irtottak, valamint a táborban végeztek különböző feladatokat. Százötven fős barakkokban laktak, az ellátás rossz volt: gyakran csak este kapták meg az ebédre szánt, kihűlt „levest”. Sok tinédzser korú rab kapott tífuszt vagy skarlátot, de gyógyszer nem volt. A gyengélkedőn rendszeresen zajlottak szelekciók: alkalmanként több mint 50 munkaképtelen foglyot küldtek Birkenauba. Helyükre újabbak érkeztek. 1944 nyarán havonta 60-90 haláleset történt. „A Blockmeister ha valakire ránézett, és nem tetszett neki, arra olyan ütéseket mért, hogy az másnap ágynak dőlt, és harmadnap krematóriumba került” – emlékezett egy 18 éves asztalos fiú Bilkéről. A tábort a birkenaui krematóriumok korábbi parancsnoka, a szadista Otto Moll SS-Hauptscharführer vezette.

When a prisoner escaped in December 1944, a drunk Moll executed 19 people as a revenge. Yet, more escapes happened. Those caught were tortured and hanged. “One day when we were escorted to the mines and a person from our group tried to flee. He had to stand all day with hands up in the air, like a stick, while the SS was beating him with riffle butts and rubber truncheons. If he dared cry, he was tortured more. He was hanged in the evening” – reported three teenagers (14, 15 and 18 years old) from Carpatho-Ruthenia.

The exact number of Hungarian children performing slave labor in various camps of the Auschwitz-complex is unknown. We do not know either how many died in Monowitz and the subcamps or how many were taken to the Birkenau gas chambers because they were incapable of working. What is sure, though, is that in January 1945, third of the 9806 Monowitz prisoners, 3103 people, were Hungarians. Hundreds were certainly under 18. In January 1945, when the Red Army was approaching, they and the other subcamps survivors were set off in death marches towards the Reichs’s western concentration camps.