Occupation, yellow star, ghetto: children’s perspectives on 1944

“I did not go to school today”

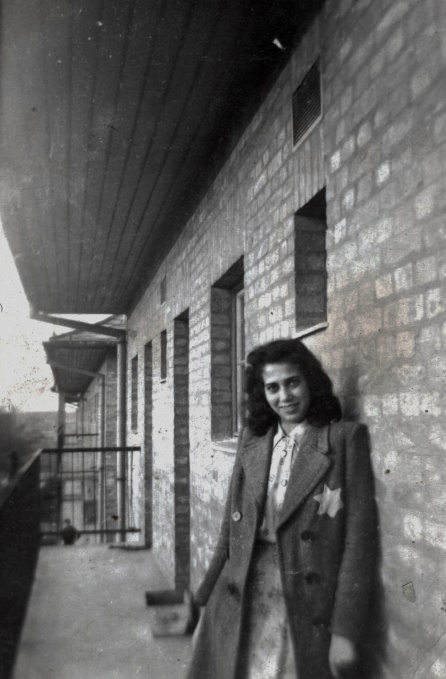

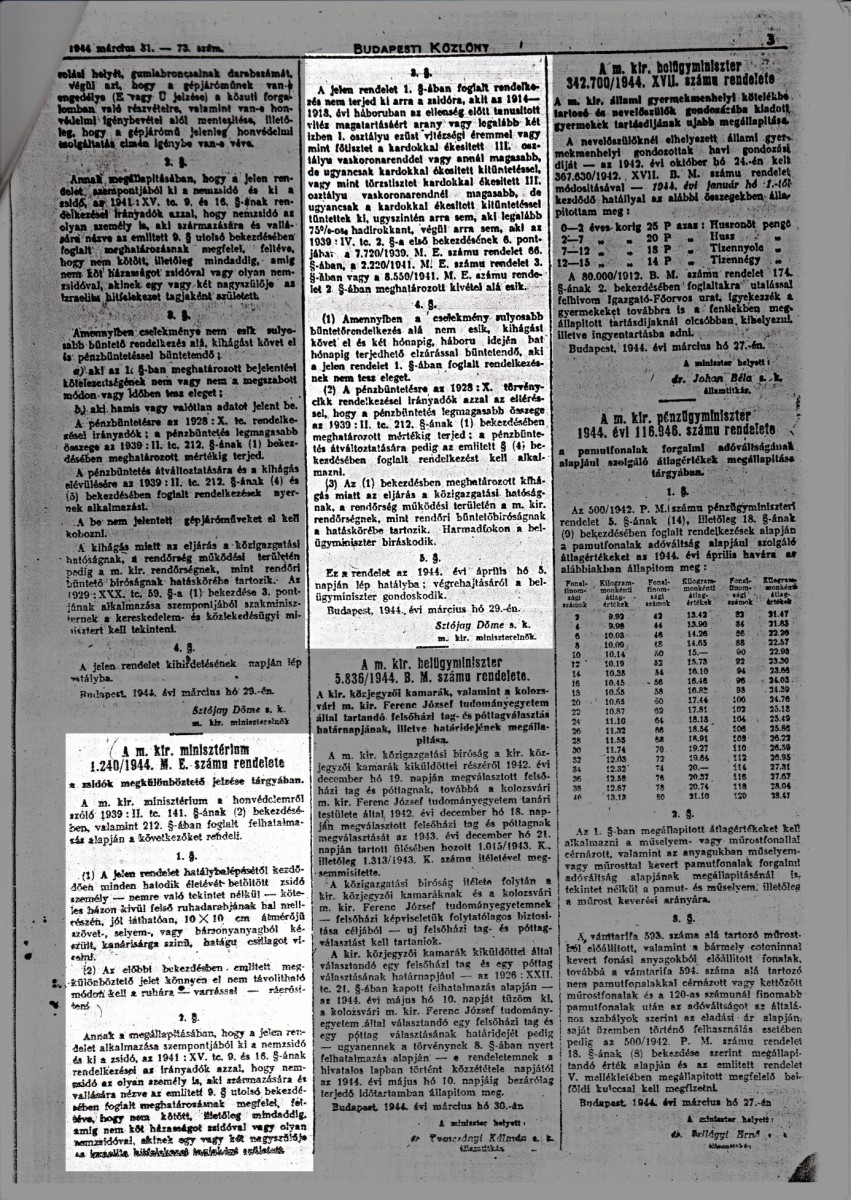

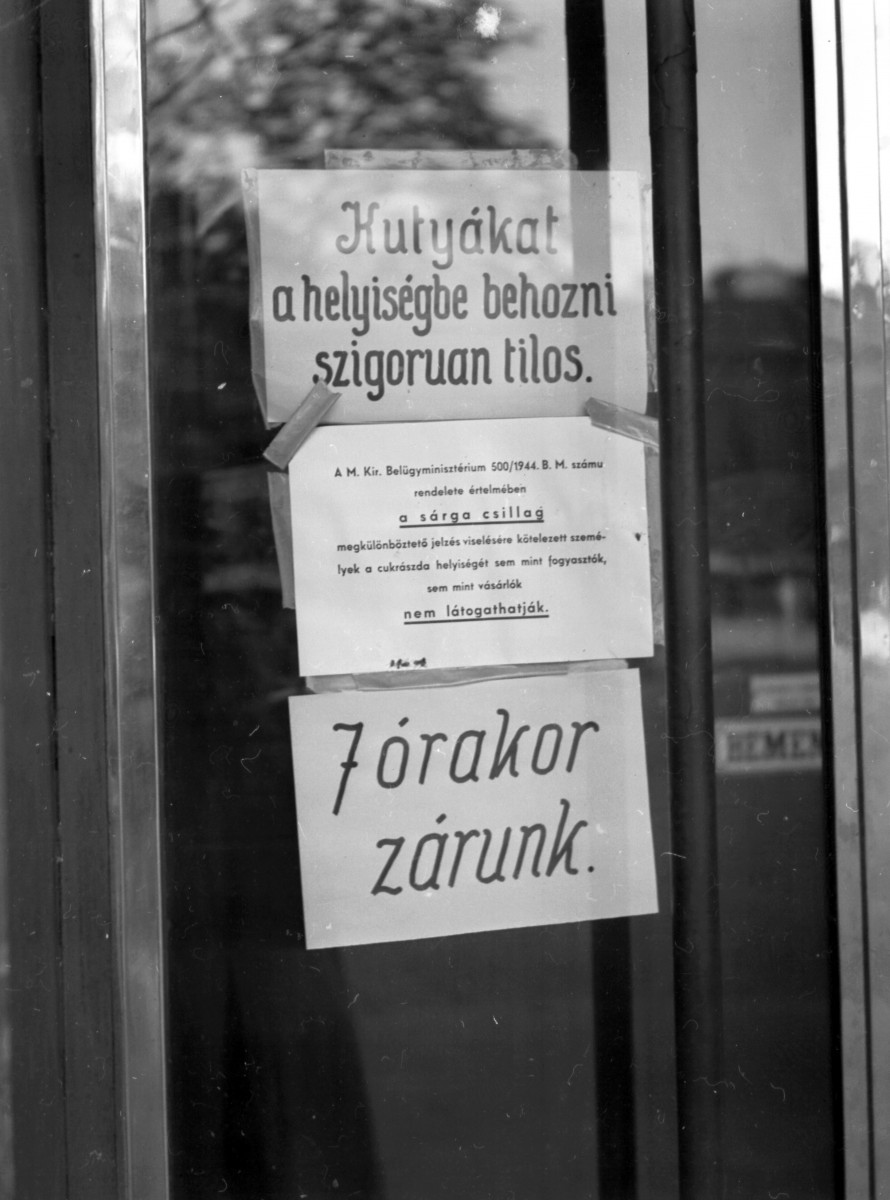

Following the German occupation of Hungary on 19 March 1944, Hungarian authorities invested immense energies into thedisenfranchisement and plunder of Jews. Their assets were confiscated, they were fired from their jobs, their travel restricted. Every Jew older than six years of age had to wear a 10×10 cm yellow star on their clothing.

“I did not go to school” – this is the opening sentence ofImreKertész’ Nobel-prize winning novel Fateless depicting the story of the fifteen-year-old Kertész in 1944-45. “I did not go to school for a whole week. Many were absent too” wrote fourteen-year-old Erzsébet Steiner from Budapest in her diary. “I hoped there would be no teaching” so noted Márta Klein also from the capital on Monday, March 20, a day after occupation. “There was” she added in disappointment.

Experiences of children and teenagers were determined by three developments in the ensuing three weeks. The school year was terminated abruptly, the yellow stars had to be patched and adults seemed helpless and distressed.

Thirteen-year-old László Kovács from Nyíregyháza was almost relieved not having to go to the local high school anymore, where senior students routinely humiliated and abused the boy wearing the yellow star. Sixteen-year-old Lilla Ecséri from Budapest revolted against the decision of her parents in defiance. The adults, although they placed the yellow Star of David, attempted to conceal it the best they could. “I do not want to hide it” as she put down in her diary on April 24: “if I have to wear it, I want to wear it openly”. Péter Lövi from Budapest was not yet 6, so he did not have to wear the star according to the official decree. He felt offended not being able to wear what he saw as“decoration”, which he felt looked nice and which the big ones and adults were allowed to put on. A young teenager, Márta Klein, on the other hand sensed what the yellow star meant. “Mom already cuts and sews the stars. I understand nothing of it. I have always been Hungarian and still am. Is being Jewish not just a religion?” Seventeen-year-old Gábor Czitrom from Kolozsvár (Cluj) was also well aware that the yellow star was not only an administrative measure but also a symbol of the humiliation and excommunication of Jews. In a recollection, he later admitted not having been offended by it though, as everyone in the town had known who was Jewish and who was not anyway. Imre Kertész’s literary self felt the discomfort only when he had to stroll down the street with his parents but had no problems with it when walking alone.

What may have disturbed children and adolescents the most was to see their parents and adult relatives helpless and incapacitated.When hearing of the yellow star decree, Éva Heyman’s grandmother had a nervous breakdown. The thirteen-year-old Nagyvárad (Oradea) girl had to be relocated to the home of a friend for a few days. This is where the star was put on “tightly, right above my heart. I spent five days at Anni’s, it was much better than at home”. The relationship of Erzsébet Steiner with her father suffered great damage when the man – obviously under the pressure of the circumstances – went berserk. On April 8, three days after the enactment of the decree, sentiments ran high at a family feud: “dad went hysterical, started pulling and beating me … I was crying like crazy. I will not talk to the old man [her father]. I just trust, that if God exists, he will provide me with better parents. They are not even parents. A mother and father treating their child like this cannot be true”. Erzsébet clearly understood though that the incident was anything but unrelated to the grim developments of the preceding weeks: “Dad is frustrated and had to direct his anger against someone.”

A world closing down

Hungarian authorities set up 350 ghettos and collection camps throughout the country between 16 April and 30 June 1944. In Budapest, as in many other towns and cities, Jews were scattered in different residential blocks, instead of being rounded up in a contiguous and fenced off ghetto. In just 10 weeks, some 650,000 people were forced into designated residence.

Forcing Jews in ghettos was done with particular brutality in the eastern and northeastern parts of the country. Children were traumatized immediately. The Kovács family was awaken by someone banging on their door early in the morning on Sunday, 16 April, the first day of the operation. “Open the door immediately, it is the Gendarmerie! Put on your clothes! Pack up!”. As everywhere else, authorities began the operations by confiscating Jewish assets, now considered national property. “The police officer first took the earrings from Mom and Évi” – remembered László, then thirteen. “You will not need them at the place where you are going, filthy Jews”. In Nagyvárad, the officer noticed a thin golden necklace around Éva Heyman’s neck. She kept the key to her diary hanging on the necklace. “This is not private property anymore, it is national” yelled the policeman. Like hundreds of fellow Nyíregyháza Jews, the Kovács family was first taken to the school of the Jewish community by law enforcement, who kept beating the people indiscriminately. One of them was particularly wild. He beat up László, just a young teenager, with a wooden stick multiple times. When his mother tried to protect him, he punched her in her face. “So many poor families, having to see each other’s suffering and hearing the children crying leads to panic. Crying, hysterical, tumultuous scenes.”

Suddenly, Jews found themselves in radically shrinking spaces. Congestion was nearly unbearable in most places. In Pécs, three square meters of space were available per person, two in the ghettos of the Debrecen gendarmerie district and only one in Nyíregyháza, where there was a one-story farmhouse, where 198 people were crammed. Some two dozen persons shared one room in Máramarossziget (Sighetu Marmației). Only two square meters of space were available per person also in the ghetto of Dés (Dej).

“I fell for one of the boys”

Children did not always see the congestion as a tragedy. “According to the decree – reads Éva Heyman’s diary – 16 persons are to reside in one room, but the room is small, we cannot move, although we are only the fourteen of us together. When it was dark, we laid down on the mattresses. I cuddled with Marica [Éva’s cousin and friend, who died in Éva’s hands in Birkenau a few weeks later] and, believe or not, both of us were almost happy, my dear diary. As strange as it may be, we were together with everyone we loved”

The following desperate lines were written by fourteen-year-old Erzsébet Steiner from Budapest: “Dear Diary … the ghetto order was announced today. We are in serious uncertainty. I would like to die. This may happen”. Her tone became more relaxed by mid-July “I am writing here in the new apartment where we had to move. Thank God, my apathy is gone. There is a good company here, I think I fell for one of the boys.” Erzsébet was not the only one whose social and emotional life was invigorated in the ghetto, despite the hardships. Éva Heyman was happy to see that her until then unattainable love, Pista Vadas was assigned to the same building as she was. Éva Weinmann from Budapest had to move into a so-called mixed building, in which some apartments were occupied by Christian residents. As the sixteen-year-old adolescent put it in her diary in disappointment, the two seventeen-year-old Jewish boys in the building were “ugly”, while “there are three handsome goyim [gentiles], but they do not care about me … this is the selection”.

The civic order of the era before the occupation disintegrated overnight, rules fell apart. Adults’ focus was directed at survival, acquisition of water, food, medication, avoiding the brutality of authorities. Forcing Jews into the ghettos began in the spring and continued into the long and hot summer of 1944. Children “were out in the courtyards of ghetto buildings the whole day”, wrote Nagyvárad journalist and survivor, Béla Zsolt after the war. “They had to get up at five in the morning, just like their parents, as per the order, and they always were in the way of adults. They played their pranks as for many children, especially those coming from wealthier families, the ghetto offered a level of freedom they had not enjoyed before in the confines of strict parental control and rules enforced by nannies”. Teenage “boys and girls hid in the bush, went up to the attic, or to the bathroom together – early puberty broke loose”. Mária Ember, thirteen years old at the time, also remembered the Kunhegyes ghetto as a place where children, although always hungry, enjoyed the sudden freedom and the collapse of the discipline previously enforced on them by the authority of adults.

In some cases, parents made heroic efforts to uphold a seemingly normal life. The father of thirteen-year-old László Kovács was separated from his family at the courtyard of the Nyíregyháza Jewish school, the first collection point.László was put in the ghetto with his mother and sibling. Others were exposed to the same treatment. The four mothers amalgamated the four single-parent families into one big twelve-member family. “As the living areas were appropriated, our mothers took care to organize ourselves and arrange things in a way that the 12 of us were in the end accommodated as one family” – wrote Kovács, the sole survivor of the group of 12 after the war. The mothers kept the 4×4-meter room tidy, shared the task of supervising the children among themselves, organized study groups to keep them busy during the day. “I still admire these four slender, beautiful and educated young women.” – remembered László.

In the ghetto

As conditions fast deteriorated, these efforts failed, and the joy of the “vacation” was a thing of the past. Food was in declining supply, bathing facilities lacking, people were soon infected with lice and epidemic broke out. Authorities began to liquidate the ghettos in many places. Before deportation, Jews had been taken to collection camps where conditions were even worse. Hardships gradually took their toll on people’s mental and physical health and immune system. “We saw our loved ones, friends shrinking, weakening, growing thinner and thinner by the day. Mothers could not breastfeed anymore. The skin on the face of the small ones was almost translucent, their beautiful eyes hollow” – remembered Kovács about the collection camp in Simapuszta.

Even before the ghettoization gendarmes had often beat up people, the delirious rush for valuables however began with the setting up of the ghettos and collection camps. In the torture rooms wealthy or assumed to be wealthy people were interrogated brutally to make them reveal where they had hidden their valuables. The specialty of the Kolozsvár law enforcement was a torture method focused on the testicles, so was that of the Nagyváraddetective unit. In Miskolc, gendarmes hanged victims upside down, and beat them while in that position. Many were forced to drink salty water. Several people died of the torment, others suffered a nervous breakdown as a result of what they had gone through.

Authorities did not spare the children and adolescents either. Many had to see their parents tortured. Whips, pizzles and sticks were used to beat people, often before the very eyes of their children as in happened inKolozsvár and Nyíregyháza. According to the recollection of BélaZsolt, a young woman asked for his advice as to what she should do: a gendarme promised her that her old and sick father would not be tortured if she sleeps with him. Zsolt refused to resolve the dilemma. The girl finally did what was requested of her, yet, her father was beaten to death.

The Hungarian Royal Ministry of the Interior aspired to plunder Jewish property to the fullest. They wanted to avoid Jews hiding their valuables thereby depriving the state budget of income. They were not deterred to look for rings, gems, gold in body orifices of adults and children. According to the order of Deputy Minister László Endre, Jews in the camps and ghettos had to undergo cavity search. As per the order, not even children were exempt of this humiliating and painful procedure. This included a rectal search in the case of men and boys and genitals of women were not spared either. Even those who survived Auschwitz remembered this as one of the most traumatizing experiences. The author Béla Zsolt was hiding in the ghetto hospital, the former house of the Chasidic rabbi of Nagyvárad and saw the horrible condition of people who underwent the cavity search. “Seventy-year-old women were crawling through the door like thousand-year-olds, small girls ran out, their faces red like blood, their eyes black and baggy, as if they had wanted to run out of the world”.

In many places, gendarmes and officers were not experienced enough to professionally conduct cavity search. Local authorities therefore deployed midwives and nurses – at the cost of the Jews of course. By no means was it intended to raise the level of hygiene or lower the pain. In Pécs, Szászrégen(Reghin), andDés the virginal membrane of young girls was torn open, many of them were exposed to serious infections by the dirty hands. A total of 10 women conducting cavity search in Székesfehérvár used two pairs of rubber gloves to examine the vaginae of hundreds of women. Not even small girls under six years of age were spared here.

Hungarian history hit rock bottom, a point not easy to surpass; by the order of the authorities, state officials searched for “national property” in the body orifices of small children.