Hungarian children in Nazi concentration camps

In the summer of 1944 Hungarian Jews were deported to the Auschwitz-complex in such large numbers that the camp administration could not cope. Therefore tens of thousands of Hungarians had not even been tattooed. Due to lack of space, 25,000 – 30,000 female prisoners – among them thousands of teenage girls under 18 – were assigned to a half-built section of Birkenau (BIII). This part of the camp was dubbed “Mexico” by the prisoners due to the specifically dire circumstances and lack of running water and a sewage system.

Most of the women and girls crammed here were not even given prisoner uniforms: they had to wrap themselves in nightgowns, ragged evening dresses and blankets. Further thousands were taken to the transit camps for men (BIId) and women (BIIc).

The emaciated and the sick were selected out by the SS physicians on a weekly basis. During the process, women and girls had to march naked in front of the SS. Those incapable of working were taken to the crematoria on trucks. Smaller groups were shot dead by one of the SS men working there, while more populous groups were murdered with gas. The mass of tens of thousands of prisoners in “Mexico” and the transit camps was used a labor force reserve by the SS. Those who survived the days or sometimes months of wait were deported to perform slave labor all across Europe. They were not registered or tattooed.

Hungarian child and adult slaves were scattered in hundreds of concentration, labor and forced labor camps, plants and factories. Thousands were taken by the Nazis to the subcamp system of the nearby KL Gross-Rosen, Flossenbürg and Dachau in Bavaria or Mauthausen in Austria. Further thousand disappeared in Northern Germany in KL Sachsenhausen or KL Ravensbrück, the women’s camp. Hungarian Jews were taken as far as Warsaw and the Baltic Sea (KL Stutthof) in the north and east, and even further: to Riga in Latvia and from there to Kaunas in Lithuania. The SS transported additional thousands to the far western edges: to the camps of the Neuengamme complex as well KL Natzweiler-Struthof in Alsace.

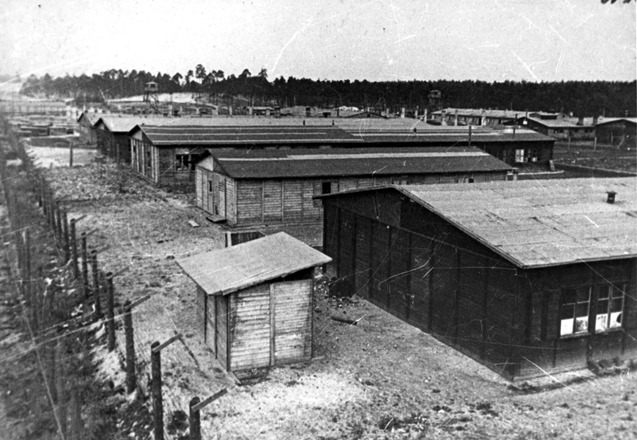

Arbeitslager Dora in Thuringia was set up in 1943 as a subcamp of KL Buchenwald because Hitler ordered the relocation of armament industry below ground from the surface. The prisoners had to dig tunnels and hangars into the mountains. The Nazis erected immense factories here where the prisoners were supposed to build the “wonder weapon”. In the fall of 1944 Dora was reorganized as an independent concentration camp by the name KL Mittelbau.

The first Hungarian Jews arrived from Birkenau in May 1944. The SS took more than 500 prisoners to the Ellrich subcamp. This site had the longest working hours. Lice were teeming because the prisoners were not given clothes for months. According to a surviving witness, the Hungarians soon became “skeletons with scary heads walking unsteadily”.

Many Hungarian children between the age of 11 and 15 were brought to the Ellrich subcamp. The memory of their suffering haunted the survivors for many decades to come. The kids were assigned in adult work commandos but received reduced child rations. They were clearing the rubbles of a factory or cleaned reeds and dried swamps with their bare hands, standing inthigh-highwater. Adult prisoners separated a corner for them in Block 5 in order for the 20 kids to stay together. They slept on blankets spread on the ground. “Throughout the blackout (from around eleven o’ clock at night until five o’ clock in the morning), the voices of these children could be heard whimpering, and, it seemed, calling out for their parents who would never come…The whimpers of those children are my most distressing memory…” – so remembered later a French deportee. The Nazissystematicallyworked to death the little slaves.

Thousands of men and boys from Carpatho-Ruthenia and regions around Budapest were taken to a new camp erected on the territory of the former Warsaw ghetto destroyed during 1943. According to seventeen-year-old Dezső Weingarten “life here was heavenly compared to Auschwitz”. Certain commandos received half a kilogram of bread and 1.5 liters of soup a day – twice as much as in Birkenau. Similarly, the treatment and labor was also better. József Fischer, 16 years old, and his fellow prisoners were clearing rubble in the former ghetto. The Polish foremen “treated us humanely”.

Ernő Rath and his 16-year-old younger brother, József, traded gold and jewelry found in the rubble of the former ghetto for food. The fourteen-year-old boy from Munkács, Izrael Szmulovits, later remembered that the SS guards treated them decently, but the capos recruited from German criminals “did what they wanted to us, they beat us up as they pleased”. Sixteen-year-old Dávid Moskovits and his fellow prisoners were brutalized by both the SS and the German capos. Mandel Klein and other prisoners were forced to pull the SS’s car. Klein even lost four teeth when a guard punched him in the mouth.

Most of the hundreds of women deported by the SS to the Vaivara camp complex in Estonia were also minors. Family members of fifteen-year-old Fáni Fuchs were deported to Galicia already in 1941 by the Hungarian authorities as they were deemed “stateless”. They escaped the gas chambers of the Belzec extermination camp and returned to Hungary. Fáni, still only 17 years old, was separated from her parents and was taken to subcamp Goldfields of KL Vaivara from Birkenau in the spring of 1944. They took off for the forest at 5 am and they worked all day in knee-high water. “We cleared forest, cut down large pine trees … It was very hard labor. When we returned to the camp we could not feel our hands. … We were close to death.” Yet, here they could still cope and everybody stayed alive. However, when in a few weeks they performed the same labor in another subcamp (Lagedi), “many of us died and even more fell ill”. Eighteen-year-old Judit Falikovics from Nagyszőlős was also taken to Lagedi. They had to sleep on the bare ground as they were not even given straw mattresses. A log fell on her feet in the woods but fortunately she was discharged from the hospital after two weeks.

The SS transferred thousands of Hungarian Jewish girls and women from Birkenau to the concentration camp Riga-Kaiserwald set up in the Latvian capital. At first, Adél Markovics, 17 years old, and her mother were shoveling sand close to the main camp. Later they were assigned to a garden allotment of a nearby subcamp and then they were evacuated to another one (Dundaga I) as the Soviet troops were approaching. During the transfer, they were beaten up and starved. Soon they had to take off from here as well. The SS took them to an ammunition factory in Windau where they had to load heavy ammunition cases. “We had to bathe in the sea where we had to wash ourselves naked in front of the SS men who were taking photographs” – they remembered the humiliating situation after the war. The Grünberger sisters, 15 and 16 years of age, tried to see the silver lining of the bizarre situation. “We could bathe in the sea after work and this was really good”. Meanwhile fifteen-year-old Gitta Freumotivs and her sister, fifteen-year-old Relli were threatened in one of the factories: those who would not work “will go to the crematorium”.

Thousands were taken by the SS to KL Plaszow – the camp close to Krakow featured by the Oscar winning film Schindler’s List. Most of them were young women and teenage girls, but a few hundred men and young boys, aged 13 to 17, were also transported here. According to seventeen-year-old Hajnal Herskovics, at first the Plaszow camp seemed to be more bearable than Birkenau where there were no bunkbeds or drinking water: “the only good thing [in Plaszow] was cleanliness, we could take a shower every day and drink good clean water which made a lot of difference”. Later the crowd increased and four or five prisoners were sleeping on one bed. In other barracks, however, “there were a lot of bedbugs and lice, everything was filthy and dirty” – remembered a survivor.

Boys under sixteen were assigned for constructions to work as mason apprentices. According to Haszkel Fischerlovics, only 13 and a half at the time, they received relatively good food supply: “I worked 10 hours a day. I have to admit the food was very good: a quarter of a bread a day, half a loaf twice a week … 30 decagrams of marmalade, pearl barley soup with meat – and all portions were sufficient”. Women fared worse. In the commando of Mária Forgács, a fourteen-year-old student from Miskolc, the food supply included “mainly only pearl barley soup and we also get 20 decagrams of bread a day and 2 or 3 decagrams of margarine or marmalade”. Teenage girls living on these rations had to shovel coal, load bogies and perform earthwork. Many were assigned to a quarry: “Work was terribly hard here: we had to drag huge pieces of stone up and down the hill without any purpose whatsoever” – remembered fifteen-year-old Fáni Stern. Reveille was at 3 am in order to have time for the roll call: “They made us work from 5 am to 7 pm; it did not matter if it was heavy rain or scorching heat, we have to suffer through the day in thin clothes, without coats. We would constantly find human bones because this was the site of the former Krakow [Jewish] cemetery which was turned by the Germans into a concentration camp”

Ibolya Kerl, who was 16 when the Hungarians deported her from Miskolc, was also assigned for work in the quarry: “We were carrying huge rocks, weighing 30 kilograms … later we dug trenches and we often would unearth coffins in the old Jewish cemetery; we saw the skeletons.”

While the number of murders in Plaszow was not skyrocketing, many Hungarian children vividly remembered brutality they experienced there. Anybody could beat up any of the kids. Sári Grünberger and his fellow prisoners were beaten by the SS guard “if we stopped for a minute” The foremen of the commando of Izidor Wettenstein, a fourteen-year-old student from Munkács, were “so bad and cruel that they beat to death a few people every day”. By contrast, thirteen-year-old Herman Adler and others were treated well by their SS guards of Romanian and Polish descent. Adler and his comrades were often beaten up, however, by capos and Jewish camp police staff. All of them dreaded the camp commander, the sadist SS- Untersturmführer Amon Leopold Göth, who became known for the world by the movie Schindler’s List. He had many people executed, while others he murdered with his own hands.

No guard dogs had been mentioned by Hungarian survivors with such an immense horror as the hounds in Plaszow. Magda Katz and her 15-year-old sister, Eszter: “The most horrifying thing was when someone stopped to rest in the hard labor for a moment and then blood hounds were set upon us who bit us all over” Commandant Göth paraded with his dogs often “The Lagerführer had two huge dogs and if we did not do something well, he immediately unleashed the two beasts to attack us” – remembered a 17-year-old Hungarian boy.

The SS transferred tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews, many thousand minors among them, to the far western rim of Germany, to KL Bergen-Belsen near the Dutch border. The actual slave labor was performed in the subcamps instead of the main camp. Acceptable conditions awaited the Hungarian girls arriving at Ünterlüss from Birkenau in the fall of the 1944. According to 16-year-old Sári Hönig, in the barracks that stood in a scenic forest “we could keep the cleanliness”. She was taken into an armament factory where first they were treated well, but they were assigned for heavy labor: “We cleared bombs and filled them with yellow sulphur powder. Our hands and hair turned completely yellow.” Despite her being only 18 years old, Mária Simkovics was promoted to be a work leader. They received 25 decagrams of bread a day and manufactured 14-kilogram bombs. The SS guards and female overseers soon banned any chat among the workers. “If the set work aim was not reached, we received beatings … the health of my comrades deteriorated so much they were incapable of working”. When winter set in, an SS female overseer did not let them wear coats. She confiscated socks and foot-rags. Those who wrapped their feet in pieces of clothing received 25 blows with a whip.

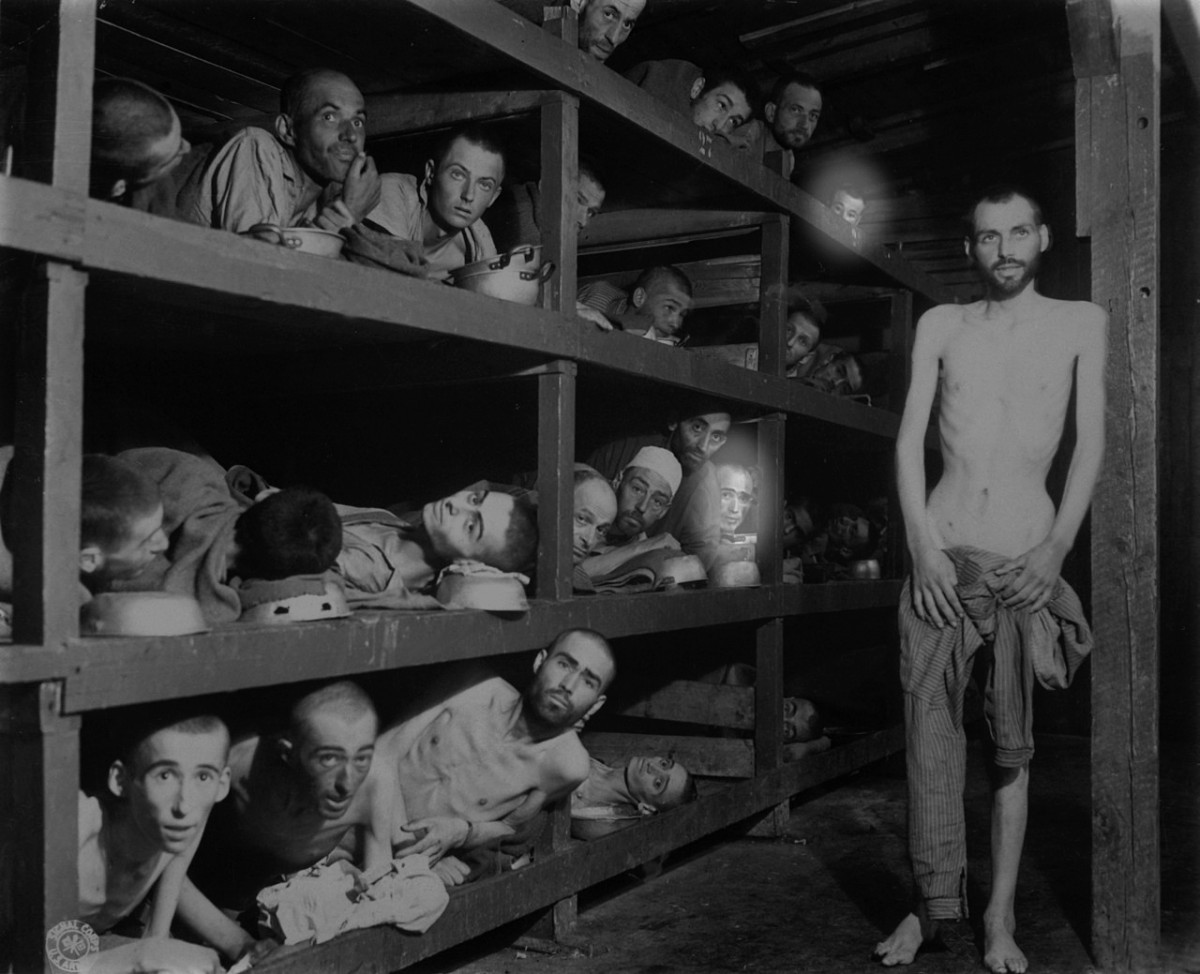

The SS did not use the gas chambers of Birkenau as of November 1944. After Belzec, Treblinka, Sobibor and Chelmno, the last extermination camp ceased to operate. However, the Holocaust continued. Moreover, in the last months of the war more prisoners died in concentration and labor camps than ever before. The Nazis were retreating from the Soviets in the east, American and British troops on the west, but they dragged the inmates of the evacuated camps along. The prisoners were chased towards the German heartlands in death marches. Tens of thousands froze or starved to death or were shot dead while trying to crawl through forests and snow fields. The concentration camps still in operation were flooded by the masses evacuated from closed camps. Crowding became intolerable. Sick prisoners carried in typhoid and scarlet fever, dysentery and TBC. Due to air raids, the collapse of the transportation infrastructure and disintegration of the Nazi state, food supply was erratic. The rations, which were meager to start with, diminished further.

The main camp of Bergen-Belsen, designed to accommodate a few thousand people, were flooded by the survivors of evacuated eastern camps by late 1944. In three months 80,000 to 90,000 prisoners were taken here by the SS. The camp administration virtually collapsed: typhoid fever broke out – 18,000 people died only in March 1945. The crematorium could not keep up, so corpses were lying everywhere. The Pollacsek sisters, 15 and 21 years of age, arrived with their mothers who died very soon. Her dead body stayed with the girls for 3 days and she was buried only after another 7 days. The Spiegel sisters, ages between 14 and 22, did not receive bread whatsoever for three weeks. They tried to survive on empty soup. Thirty to forty women died in their barrack every day. By the time the British troops arrived in April 1945, 10,000 corpses were heaped on the camp grounds, unburied.

The highest number of Jews were Hungarians in the female concentration camp of Ravensbrück in Northern Germany. A part of them were taken here from Birkenau, others were handed over by the Hungarian Arrow Cross authorities to the SS in the fall of the 1944. Eleven-year-old Judit Gertler Rosner’s mother was shot dead in the cattle car. During the day in Ravensbrück, Judit and other kids were hiding in the barracks and covered themselves up with coats. They fantasized about food and big breakfasts. Before long, Judit fell ill with typhoid fever and she was taken care of by her aunt.

The SS had brought many Hungarian teenagers to the Malchow subcamp of KL Ravensbrück to perform slave labor. The Kleinmann and Herskovics girls from Munkács, aged between 14 and 19, worked 12 hours a day in the armament factory. Their daily bread ration that used to be 20 decagrams had diminished to 8 decagrams by April 1945. This was one-third of the Birkenau portions. There were no more breakfasts and dinners, only lunch was distributed. Hungarian women and girls started literally to starve to death. Some went berserk and raided the SS warehouse. They were shot dead. The youngest Hungarian victim of the Neustadt-Glewe subcamp was Edit Klein – she was 15. It is not known if she was killed by hunger, typhoid fever or dysentery. Seventeen-year-old Rózsa Junger was assigned to work on the air field in Retzow: “We were carrying heavy stones. We had to take and hide the heavy aircrafts in the forest.” She was working 12 hours a day for 10 decagrams of bread while being beaten by SS overseers. Many of her fellow prisoners died.

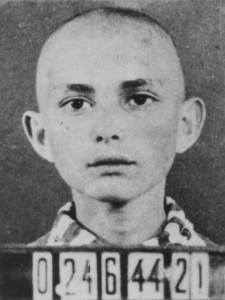

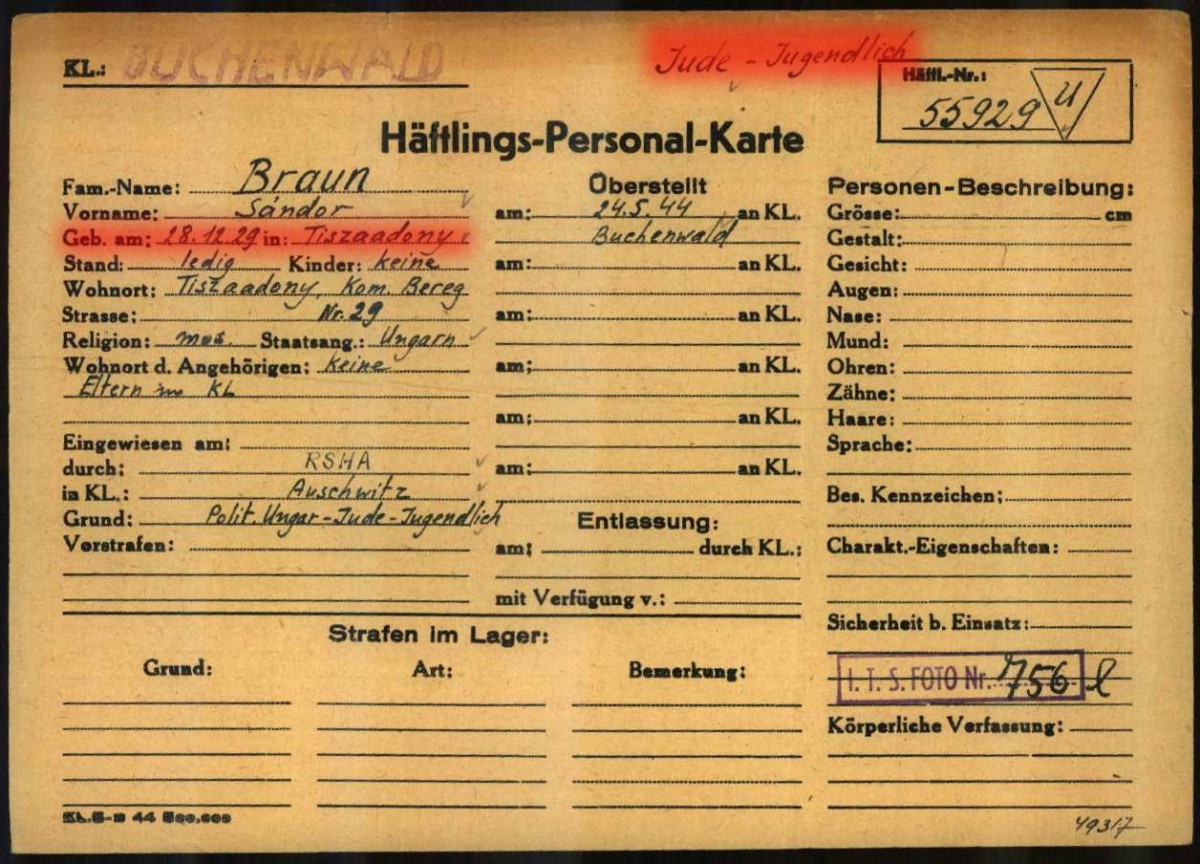

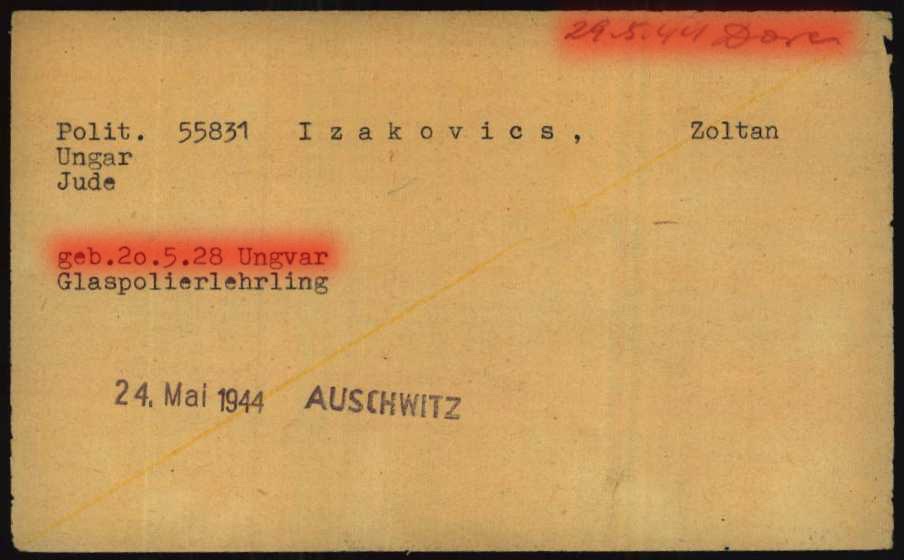

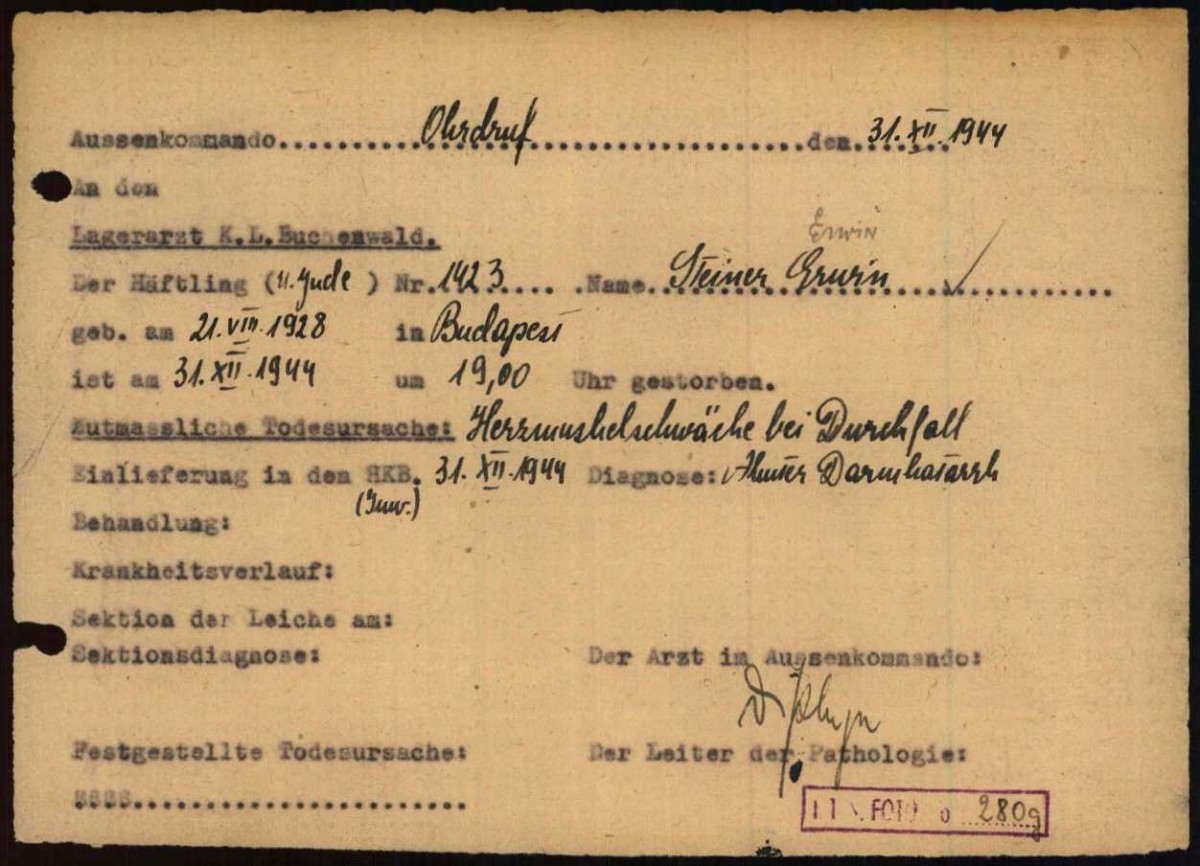

At least 33,000 Hungarian citizens were deported to KL Buchenwald. Save for a few, they were all Jewish – almost all men and boys. The number of minors is unknown, but there must have been thousands. Imre Kertész arrived in the summer. He spent only a few days in Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was not assigned a prisoner number by the camp administration and he was not tattooed either. Soon he was transported to Buchenwald. Here he received his first prisoner number: 64921.

Later he was taken for slave labor to Tröglitz-Rehmsdorf, a subcamp near Zeitz. Months of slave labor, beatings and hunger broke him physically. He was taken to the local infirmary and then they transported him back to Buchenwald. He was barely conscious, yet he was preparing to die. Instead, he was taken to one of the hospital barracks and lived to see liberation.

In the fall of 1944, the Hungarian Arrow Cross handed over tens of thousands of Hungarian Jews (people from Budapest and labor service companies) to the SS. A few groups were deported by train while others were forced to set off westwards in death marches – on foot, due to lack of train capacity.

Further thousands arrived when Auschwitz was evacuated. In the evening of 26 January 1945, the SS brough 3987 prisoners to Buchenwald.Fifty two people were dead on arrival, further 115 died on the same day. Many were taken to the camp hospital, among them Elie Wiesel (prisoner number A-7713) and his father. When the father, who could not even move, cried out loud, he was beaten by an overseer. “I did not move. I was afraid. My body was afraid of also receiving a blow. Then my father made a rattling noise and it was my name: Eliezer”. This was his father’s last word – he died that night.

Elie Wiesel was saved by the same two communist prisoners who – with help from the underground camp resistance movement – kept 904 minors alive until liberation. A third of those rescued were Hungarians.

Like the adults, teenage prisoners also wanted nothing else after the liberation but eat. The first heavy feast claimed hundreds of lives. Elie Wiesel was between life and death for two weeks, but he survived.

Those who could return home left after a few weeks of recovery, weight gain and medical treatment. Some went back to Hungary. Others, who knew they were alone, were looking for a new home.

Nine out of ten Jewish children from the Hungarian countryside were murdered. In Budapest only half of the children lived to see liberation in early 1945.