“Death or forced labor in Germany” – what did a child know?

With the exception of 15,000 people, the whole Jewish population of Hungary outside of Budapest was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau between 16 May and 9 July 1944. Budapest Jews were spared in the last moment as deportations were halted in early July. Their lives were still in danger though. In November-December 1944, Arrow Cross Party authorities (who by then ruled the country) deported tens of thousands of people from Budapest to Germany, and murdered thousands in the capital.

Like adults, children were also unaware of what awaited them in the ghettos and after deportations. At the same time however, pieces of information they did acquire was often surprisingly accurate. Márta Münzer, Éva Heyman’s best childhood friend was deported by the authorities in the summer of 1941 during the so-called Kőrösmező deportations, when mainly Jews not having Hungarian citizenship were transported to German occupied Ukraine, where German units executed most of them. Márta never returned. Survivors of the deportations, some 2000-3000 people, spirited themselves back to Hungary. A seventeen-year-old boy arrested in Budapest went through the same. He was deported with his family: “they transported us across the border and told us to go wherever we wanted to. They pushed us to Polish territory near Kőrösmező, we were only allowed to go further inside Poland, turning back was not permitted, they would have shot us to death. In Poland, we got into a forest where SS men and Hungarian gendarmes started shooting at us. I saw with my own eyes when my mother and siblings were shot to death”. He survived and fled back to Hungary alone.

Many of the survivors shared detailed recollections of their experiences. According to Éva Heyman’s mother, her daughter “was obsessed with the news, and the prospect that she and all of us she loved would face the same fate became her mania”. Following the German occupation, “the sweet dancer figure of her friend came back to her as a visual hallucination, she panicked that she too would be deported to the east and killed.” And this is exactly what happened in the end.

Others treated all this as fake news without any merit. According to the later Nobel-prize laurate Elie Wiesel, who was only thirteen at the time, the Jews of Máramarossziget simply did not believe old Uncle Moshe, who returned from the mass grave of Kamenetz-Podolsk with a shot wound. Many believed he went crazy, others assumed he only wanted to provoke sympathy and compassion for himself with his horror stories.

Many of the Polish and Slovak refugees who had fled to Hungary during the years before German occupation also told stories of the brutality and massacres taking place in their home countries. Tilu Friedmann, a fourteen-year-old student from Munkács (Mukachevo) was informed of Auschwitz by his cousin who had fled from Slovakia.

Many Hungarian families followed the BBC broadcasts and bits of information about the fate of East European Jews did surface from time to time. Mária Klein entered the following in her diary on 8 February 1944. “The Germans has already done a lot of nasty things, the London radio allegedly discloses the location from where Jews had been deported to camps and that there are no Jews in Poland anymore, they are killed with gas and then cremated”. Fifteen-year-old Helga Schneider was deported from Munkács. At the end of the arduous journey, her father quietly said: “let us take our farewell, and then held my little siblings tightly, with tears in his eyes. My father had already heard about the horrors of Auschwitz from the radio.”

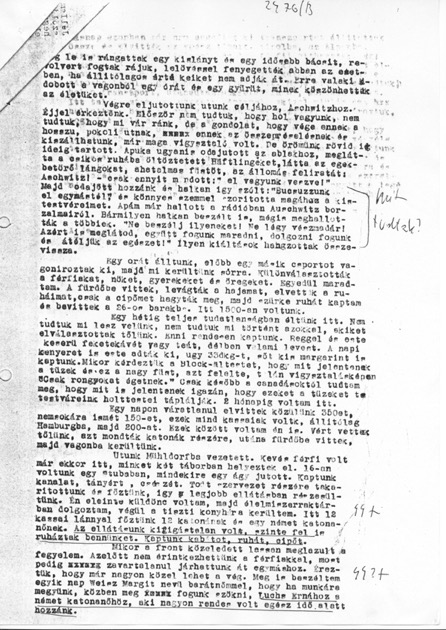

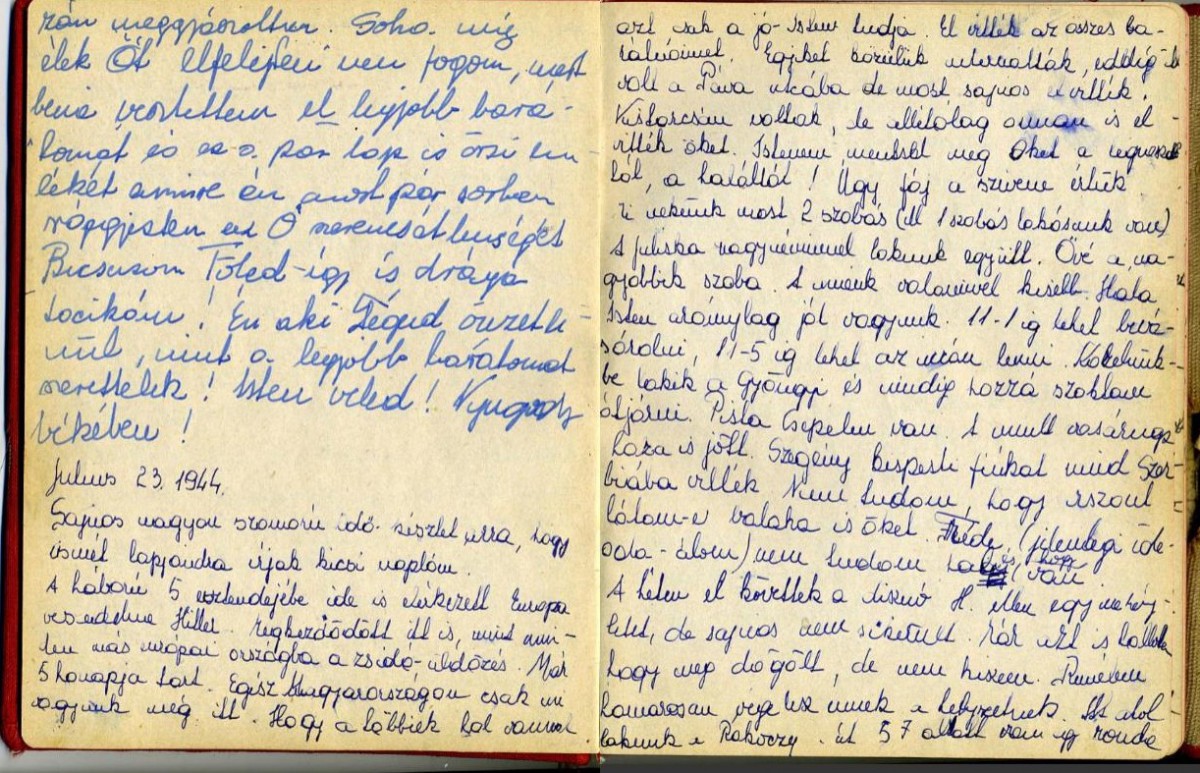

Despite the official news blackout and media censorship, deportation of the Jews of the countryside could not be kept a secret. It is therefore no surprise that Lilla Ecséri from Budapest noted as early as June 9 that “unless miracle happens, we are going to be transported to death in sealed train cars. They did that in the countryside already”. In a later entry, she added: “Prospects: death or forced labor in Germany”. The next time after January 1944, Éva Weinmann, from Budapest, touched her diary was on July 23. She briefly summarized what had happened with the Jews in the previous months: “in the fifth year of the war, Hitler, Europe’s peril arrived here. Just like in all the other European countries, the persecution of Jews has begun. It has been going on for five months now [in fact it was only three]. It is only us, Budapest people who are still around. Where the others are, only God knows. All my friends have been deported… God, spare them from death!”.

22-year-old law student, Gyula Schleiffer wrote about the general mood of the persecuted and entered in his diary on May 18 saying, “the pessimist paints the tragedy of sealed Germany bound train cars and the last experience of the gas chamber”.

Despite sporadic news, vast majority of Hungarian Jewish children, just like their parents, were unaware of what would await them in the ghettos and at the terminal station of deportation trains. Most knew nothing. Others, who had some information, hoped for the end of the war or thought such atrocities would never happen in Hungary.