Komárom and its surroundings

Jews have inhabited Komárom as early as the 13th century. As a result of the Treaty of Trianon, the city and hence the Jewish community was cut into two at the end of WWI. The area north of the river Danube (Komarno) was attached to the newly created Czechoslovakia. This part was home to approximately 3000 Neologue and Orthodox Jews. South of the river (Komárom) stayed under Hungarian reign, but merely two dozen Jewish families lived here.

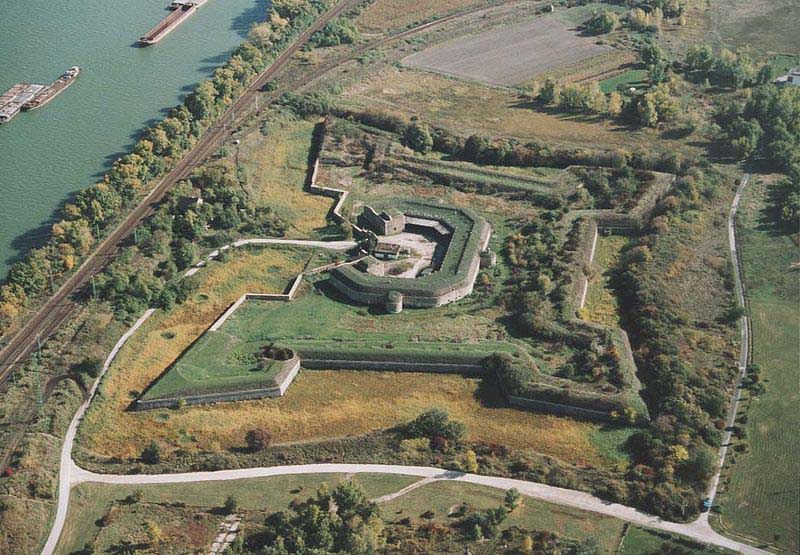

As a result of the First Vienna Award in the fall of 1938, the whole city was attached to Hungary. Hungarian authorities set up a labor service draft center as early as 1939 in one of the sections of the fortress system built in 1850-1877 on the river bank (Fort Igmándi). Out of 31,000 local inhabitants, 2743 people (8,9%) belonged to the Jewish denomination in 1941. In the following years, many Komárom Jews were drafted in the labor service. Many of them were sent to Fort Igmándi where several companies were accommodated under dire circumstances – they were beaten and humiliated by the guards and had to perform heavy earth work.

Ghetto in Komárom

At the time of the German occupation of Hungary in March 1944, 1725 Komárom residents belonged to the Neoloue and Orthodox communities. The Hungarian authorities set up the local ghetto in mid-May. Besides the Jews of the city, people from the Komárom and Gesztes Districts (provincial administrative units) were also herded here. According to the recollection of 34-year-old Margit Weiss, the gendarmes closed down the ghetto at 5 in the morning on 8 June 1944.The Jews were told that they would be taken to Germany to work and they can take a 50-kilogram luggage and food for 15 days. In less than an hour they were chased into the courtyard of the Jewish community. “Here our luggage were searched through, they took our last piece of jewelry, money and all our personal documents. In the little room next to the office they stripped us naked and examined one more time. When I asked the official, a certain Kossányi, who worked in the office to let me keep at least the document that shows that my father died the heroes’ death in WWI, he told me ‘where you go you won’t need the any documents.’”

Before long, Jews were taken from the ghetto to another part of the fortress system, the so called Fort Monostori. “The fort was the worst place we had been all throughout our one-year deportation … Jews were taken even from the lunatic asylums and hospitals and we were closed in with them … Accommodation was equally awful in this fortress. A narrow, dark spiral staircase was the only way down to these underground cellars; we lied on the wet ground teeming with lice, on top of each other. There was a communal kitchen where we got a little soup every day. Many people committed suicide – I remember two names (Miksa Fried and Mrs. Ignác Elbert), I’m not sure they died there. It was almost impossible to get water because of the crowd queuing up. There were hardly any toilet facilities. We could only wash ourselves in the Danube when early in the morning the gendarmes took us down” – remembered Margit Weiss after the war.

According to the testimony of a male survivor, 43-year-old agricultural officer from Etyek, József Klein, the ghetto was guarded by field gendarmes and appointed Jewish “policemen” and “a few deaths occurred, natural ones”.

Soon Jews from other localities (e.g. Ács, Felsőgalla, Alsógalla, Bánhida, Tatabánya, etc.) were also incarcerated in the fort and so were people previously concentrated in the Kisbér and Tata ghettos. Sources, that are at times contradictory, suggest that on 5 June the gendarmes also transported 480 inmates of the Bicske ghetto – close to 200 children among them – into Fort Monostori. Same fate awaited the Jews from Esztergom and most prisoners of the Galánta and Nagysurány ghettos (Nyitra and Pozsony counties, respectively.)

The experiences of a couple of 15-16-year-old teenagers from the Nagysurány ghetto were similar to that of those from Komárom. The youngsters coming from small villages (Bánkeszi, Komját) lived in “constant fear” after the German occupation. The Hungarian authorities arrested men, plundered families and treated Jews “in the cruelest way” possible. Their neighbors threw rocks and broke their windows. Later they were marched by the gendarmes on foot while carrying 50-kilogram luggage. They were crammed into the Nagysurány ghetto where they lived for weeks isolated from the Christian population. Finally, after yet another body search and plunder “gendarmes set us off to Fort Monostori. Here we were accommodated in moldy underground holes. We could not wash ourselves. For breakfast we got coffee, a bit of soup and 4 decagrams of bread. The Jewish Council arranged for this. We were sleeping on the ground and we were destitute during these 10 days.” József Klein remembered that the food distributed in the ghetto camp kitchen “was not satisfactory, so everyone helped themselves as they could”. In his opinion, the Mayor of Komárom (Gáspár Alapy) “acted very fair”, and “there could be no complaint against” the Jewish Council either.

Deportation

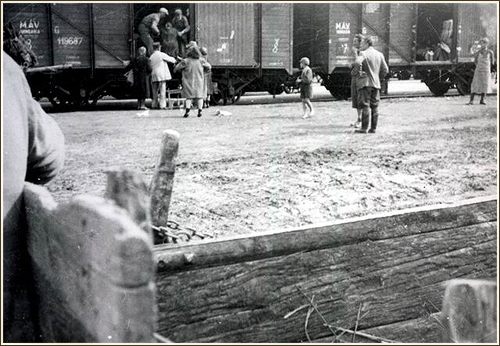

According to the recollection of Weiss Margit from Komárom, after a few days, Jews suffering in the fortress were almost looking forward to the deportation to get out of the ghetto. “Getting into the cattle car was our only desire because if the current situation was to carry on, people would have died en masse” – she remembered after the war.

But the worst was yet to come. Rumor has it that Rezső Kasztner and other Zionist leaders negotiating with the Gestapo thought that Jews from Komárom and neighboring areas would be taken to forced labor to Austria. Instead they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The 22 June letter sent by the Budapest Central Jewish Council to head of the pro-Nazi Hungarian government, Döme Sztójay, indicated 8000 deportees. The actual number was slightly lower: two trains departing on 13 and 16 June carried 5463 Jews concentrated in Komárom.

“Before departure, the gendarmes ordered us to hand over to them any valuable items we might still have on us, otherwise they will shoot us dead. Seventy people were crammed into one cattle car” – remembered a 20-year-old man from Nagysurány. Fifteen-year-old György Berger, a student from Komárom, was pushed into the car with 65 other people, “but beforehand we were searched and our money and valuables were taken away”. It was probably thanks to the positive intervention of Mayor Alapy that deportees received a loaf of bread each and buckets of water were also placed in the cattle cars. The buckets for toilet had to be obtained by the Jews.

The two trains were handed over by the Hungarian gendarmerie to the SS at Kassa (today: Kosice). The Germans distributed water, but at the same time they robbed deportees as well. “Here the SS entered the cattle cars. We had to hand over everything: soap, etc. They threatened us by shooting if we hide something, but they also reassured us that we were headed to a nice German city and we will be treated well. They also ordered us to surrender any currency we had and promised that we would receive German Marks in exchange which we would be able to use to purchase goods” – remembered a survivor. In another cattle car a rumor was started that they would be taken to farm to work east of Kassa. One gendarme reassured them that “we were going to work with carrots”.

Arrival and selection

The first Komárom transport arrived at Auschwitz-Birkenau probably in the evening hours of 15 June, after a three-day travel. Pale, exhausted, hungry people were getting off the cattle cars. “We were afraid to eat the food we brought because we thought we might not get any in Germany”. The transports were awaited by the SS and the Birkenau cleaning commando, which was dubbed “Kanada” in the camp slang. “When the cattle cars were opened, men in striped uniforms appeared and told us to leave all luggage behind; we could keep only the clothes we had on. We saw our luggage being loaded on trucks – obviously we never saw our stuff again” – remembered Margit Weiss. According to a male survivor, members of the Kanada working squad were Polish.

Soon the selection commenced. According to 16-year-old Olga Engelmann and other child survivors, the SS men used sticks to “direct the elderly, the sick and mothers with children to the left and youngsters to the right.” Fifteen-year-old György Berger observed that first men and women were separated which was followed by the separation of those capable and incapable of working. József Klein was holding his little boy’s hand and both of them were sent to join those fit to work. “My wife was with a little girl I didn’t know, she led her by the hand and she was not warned that this had fatal consequences and hence they were not sorted amongst the laborers”.

The Komárom transport was selected by SS Captain Dr. Josef Mengele: “I clearly remember that Dr. Mengele, the famous selection physician, pointed towards the center of our row and my two siblings and me were sent to the left. My fourth sibling, who was still young, was sent to the right with my mother.I think this happened because my sibling held my mother tightly as they were walking. I thought I would join my family later, but unfortunately I have been waiting in vain until today. I don’t know what happened to them. Later I talked to eye-witnesses who worked close to the crematorium and they unambiguously told me that those sent to the right were taken to the gas chambers on the very day and then burnt in the crematorium.”

Auschwitz through children’s perspectives

Out of 5463 Jews deported from Komárom, ca. 1000-1500 people were under 18. Most of them, those under 12 to 13 years, were murdered on the day of their arrival. Mostly those survived who claimed to be older by 2-3 years than their actual age. The survivors of the selection at the ramp were sent to the camp.

“…The events followed in a movie-like sequence: bath, shaving off the hair, my good clothes were taken away and I received wooden clogs in exchange of my good ones. We were transformed so much that I could not even recognize my sister” – remembered one of the teenage girls.

They had to survive the following weeks crammed into barracks that housed 1000 prisoners. “Like herrings, were sitting and squatting on top of each other.” Reveille at 3 am, followed by roll call (Appell) that took hours which the prisoners had to stand through in thin clothes, freezing. The roll call torture was repeated in the late afternoon. The food supply consisted of “black nettle soup, bread in the evening with some second servings”.

Seventeen-year-old Olga Schwartz from Csornok and 18-year-old Ilona Deutsch from Komját were sleeping in one bed with two other girls. The daily routine was disrupted by the horrors of recurring selections when SS physicians sent the weak to the crematoria and the strong to other camps to perform slave labor.

After entering the camp, fourteen to sixteen-year-old boys from Komárom were selected again: they were locked up in a separate so called children’s barrack where they spent the next two months. They were under quarantine because the camp was engulfed by a scarlet fever epidemic. Finally, in mid-August 1944, a German engineer arrived: “He told us to sign up if we wanted to learn how to work with iron. As we all wanted to get out of there, all of us (880 boys) signed up.” The engineer took only 60 of them.

They ended up in the Eintrachthütte subcamp, located 40 kilometers from Auschwitz, and worked in an armament factory. “Compared to Birkenau we were very well off in the cannon factory” – remembered György Berger after the war. Instead of 20 decagrams they were given half a kilo of bread with margarine and a small piece of salami. As opposed to one deciliter of coffee they received in Birkenau here they could drink as much as they wanted and they received marmalade twice a week. They had to work 12 hours, but they could take two resting breaks. Their ragged clothes were exchanged and fortnightly they received clean underwear. The testimonies of other Hungarian teenage boys paint a darker picture of the place. During work, the prisoners were beaten by the German foremen, capos and SS men. If they did not perform as they were expected, they received 25-50 blows with a rod. As a punishment for smuggling, a 15-year-old boy from Carpatho-Ruthenia had to stand erect between two rows of electric barbed wire and then he was locked up in a flooded cell. Those who tried to escape were executed. Every week 10-20 people died in the camp hospital. Those with lung diseases were sent back to the Birkenau gas chambers.

A boy from Nagysurány was assigned tattoo number A-14353 and then he was sent to the nearby Auschwitz concentration camp. He worked in a quarry, an armament plant and eventually he was taken to a construction site: “When we built the bunkers, we saw a female transport on the road headed to the bath. We were not allowed to contact them, but I took a glance of my mother. I started to cry heavily and not minding anything I ran up to her. My mother managed to give me a piece of paper on which beforehand he wrote down what had happened to her. On another occasion I sent her a letter and some bread, but unfortunately an SS caught me and took the letter away. He did not read Hungarian and he looked only the greeting that said ‘My sweet Anci’ [term of endearment for “mother”]. He thought I wrote it to a girl, but others translated the letter to him so he did nothing.” József Klein, who was assigned prisoner number A-14452 worked at the same place. To his luck, soon he became room supervisor (Stubenӓltester). However, he was separated from his little boy who stayed in Birkenau.

Komárom Jews in Nazi camps

People who were deported from Komárom to Auschwitz-Birkenau and found capable of working (therefore not murdered on spot) were scattered all throughout the Third Reich. So far we have identified three dozens of concentration and labor camps as well as industrial plants where they were taken to by the Nazis.

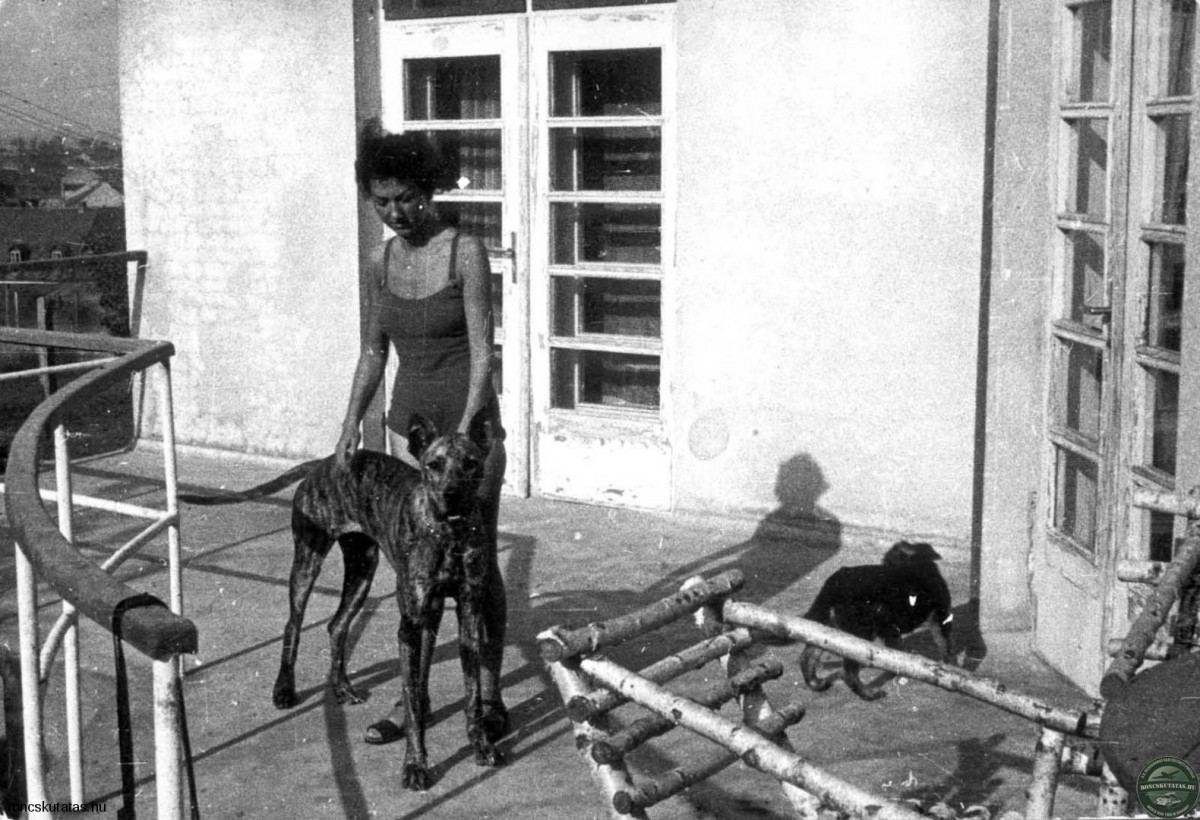

The already mentioned young girls who came from villages around Komárom were transported to the Plaszow concentration camp near Krakow. They worked in a quarry and “we were beaten heavily”. They had to work 12 hours a day. The most fearsome person was SS-Obersturmführer Amon Göth– known for the public from the movie Schindler’s List. “The SS commandant came and went on a white horse” – they remembered later.

Similarly to other survivors, the Komárom girls were also terrified of Göth’s trained dogs. “He was escorted by a blood hound. If he noticed that someone stopped working for only a few seconds, he set the dog upon us.”

Later the girls were taken from KL Plaszow back to Birkenau. They were officially registered only then: the numbers A-19305, A-22352, A-22353 and A-22544 were tattooed on their arms. Later the SS transported them to Kratzau, a subcamp of KL Gross-Rosen, where they were performing slave labor in an armament factory until liberation.

Many women and girls who earlier were incarcerated in Fort Monostori were eventually taken to the Stutthof concentration camp on the shores of the Baltic Sea. Before long, from here they were distributed into labor camps set up around Stutthof. Due to the extraordinarily dire circumstances and the brutal treatment of the guards, many of them died. The number of victims is yet unknown.

Many Jews from Komárom and the surrounding areas were deported to Buchenwald. József Klein and others arrived in February 1945 in open train cars – despite the falling snow. By that time the main camp had been paralyzed by air raids and flood of prisoner transports taken here by the escaping SS. Klein’s group was waiting for disinfection and new clothes for days – they were naked all this time. “We were sitting completely naked for three and a half days until the water pipe was repaired and it was finally our turn. During this time a lot of people died – we were sitting on corpses.” Soon they signed up for a transport and the SS took them to Bisingen, one of the subcamps of the westernmost camp complex, KL Natzweiler. Thirty eight percent of the 4200 prisoners died in the camp that was located close to the Swiss border.The Hungarians worked here in knee-high mud with very meager food supplies.

Other Jews from Komárom were taken to subcamps of the Buchenwald main camp. They performed slave labor in at least eight smaller camps (Berga-Elster, Duderstadt, Flößberg, Langstein-Zwieberge, Magdeburg-Rothensee, Markkleeberg, Rhemsdorf/Tröglitz, Schlieben). Many were killed or perished here.

Some men and boys worked in the underground constructions of the Langenstein-Zwieberge subcamp. They were carrying 50-kilogram cement sacks. “So many times young, thin teenagers collapsed under the weight of the heavy sack … When a sack was dropped, it cracked open and the cement spilled out. If a sack was finished, the man was finished. There were days when more than 50 people were beaten to death” – so a survivor remembered of the child slaves.

In the Junkers factory of the Markkleeberg subcamp, 1300 Hungarian Jewish women and 250 French female prisoners worked. In the ranks of the Hungarians were 12-14-year-old children as well. The SS commander of the camp, the sadist Knittel, ordered the prisoners to kneel in the snow during punitive roll calls in the middle of the night. Some of them froze to death. Others were lined up in the yard naked. According to the recollection of a 17-year-old girl: “It was their Sunday entertainment to watch us as we were loading coal to the freight cars in one thin dress without tights” Pregnant women were sent to Bergen-Belsen; newborn babies died in a few days. Some prisoners committed suicide, others fell ill and died. Finally, on 13 April 1945 the SS started to evacuate the camp. 1539 prisoners were set off to the Theresienstadt ghetto. The weak were pulled on carriages by those in better shape. Those incapable of walking were shot by the SS. Eventually only 703 prisoners arrived – the others escaped or were killed.

A boy from Komárom was taken by one of the transports to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. “We have not received any food or drinks during the whole journey. An awful lot of the people died or went insane. We noticed that madness took over a person when he started to strip down. Then in the evening and during the night madness was launched and he wanted to kill everybody”. The only reason he survived was that Czech workers threw food into the freight cars on the way.

Many people dragged away from Komárom were killed in the Bavarian camp of KL Dachau or in one of its subcamps (Allach, Augsburg, Kaufering I – Landsberg, Landshut, Mühldorf I -Mettenheim, Mühldorf -Waldlager, Ötztal, Kaufering VI -Türkheim, Riederloh etc.).

A group of boys and men deported with the second Komárom transport were shortly sent from Birkenau to the Allach camp. They started to work after a few days spent in the quarantine. “Work was so hard that it was called Totenkommando [death commando]. People were killed off every day. We carried cement to the second and third floors. We were constantly beaten without any reason. We had to constantly run with the heavy sacks on our backs and if you did not run then you were beaten up with rods and riffle butts.” – remembered a survivor.

Another group was taken to the Mühldorf subcamp. The first impressions were positive: “We were resting in a beautiful pine forest and lectured by a jovial Bavarian soldier: are there any locomotive drivers or crane conductors among us; he is worried if were capable of carrying 50-kilogram cement sacks. We are enthusiastic: of course we are! We take a bath. We see Hungarian girls … they are in great shape, they reassure us: the food is good and there is hot water as well. We take a fantastic bath … We settle in the barracks. There are beds, what a paradise! We are gaining some strength from the food that’s better than in Auschwitz, but what followed was horrible …” – remembered one of the few survivors. “Loading 50-kilogram cement sacks is a terrible work. I did not realize that cement was so active chemically – it dries out your hand, the skin is ripped, you have to work with bloody hands … We have to carry the bags up 35 stairs. There is hardly any food … I see people falling. The father of my colleague had been here for two months. He is incapable of working. Tomorrow’s transport will carry him back to Auschwitz, to his death.”

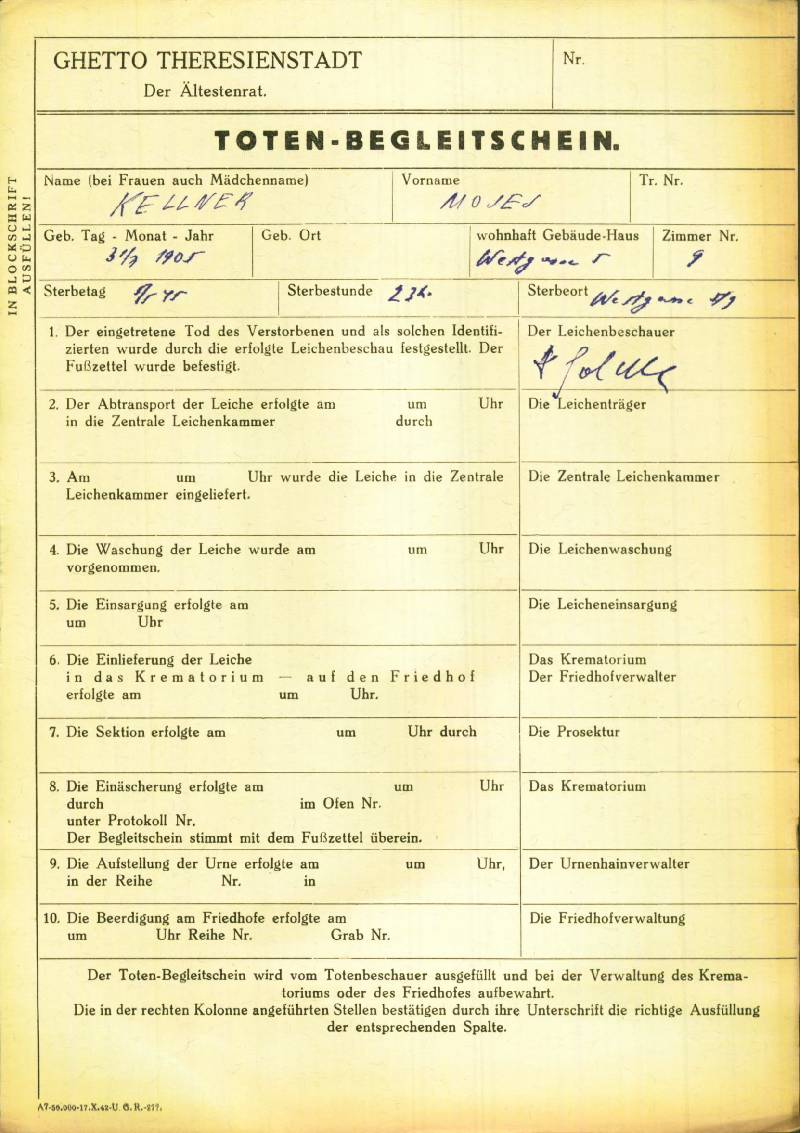

In April 1945, during the evacuation of several camps, the SS sent Hungarian prisoners to the Theresienstadt ghetto in the Czech territories with multiple transports. Komárom was registered as permanent or last place of residence for at least 21 of them. Additional three put down Tata. With one exception, they all survived and saw liberation.

Many children survived too. Edit and Lea Stern were born in 1930. During selections they claimed to be 18 years old. Eszter Rubinstein was also under 18 when deported. Olga Grünhut did not reach 18 even on the day of her liberation, and Rózsi Goldstein from Tata was merely 16 at the end of the war.

Majority of those 5463 people deported from Komárom were murdered by the Nazis in Auschwitz-Birkenau on the very day of their arrival. Most of those fit to work and transported to further camps died in the camp systems of Buchenwald and Dachau. According to information available at this stage, ca. three dozen Komárom residents were killed or perished in Flossenbürg and its subcamps (e.g. Hersbruck, Leitmeritz, etc.). The number of Komárom victims was somewhat smaller in the camps of KL Mittelbau, mainly in Ohrdruf. More than a hundred people have not returned from Mauthausen and its subcamps in Austria.They were murdered predominantly in Gusen, Melk, and the “euthanasia castle” of Hartheim. Some of them died in the Ebensee or Gunskirchen subcamps. Due to scarcity of data we know little of the fate of those deported to Bergen-Belsen, Gross-Rosen, and Sachsenhausen.

The research is to be continued.